The incidence of geomembrane whales/hippos in surface impoundments containing various types of liquids is, unfortunately, not uncommon. See, for example, GSI White Paper #30, which discusses corrective actions after they occur. This article, however, addresses the situation before it occurs.

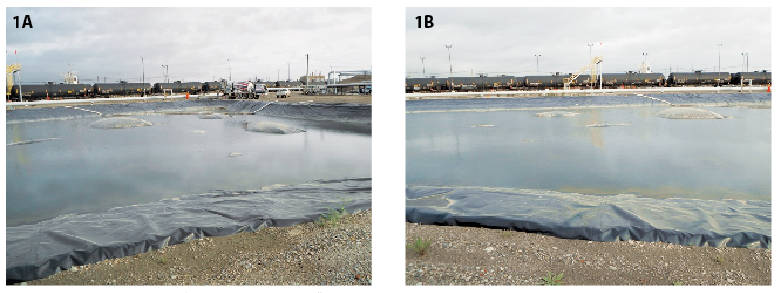

Clearly, the presence of a geomembrane creates anomalies in the underlying subgrade that can cause rising gases to impinge on the bottom of the geomembrane. In turn, this can cause the geomembrane to rise to the liquid surface and even above. Obviously, the geomembrane is being forced upward by the captured gases in an ever-increasing manner. Figures 1A and 1B show some of many such whales/hippos at one of two surface impoundments to be described.

The solution to avoid such occurrences is simple. What is required is an underlying permeable material that captures and laterally transmits the gases to and up the side slopes and then vents them to the atmosphere. A sand layer is certainly possible, but geosynthetics offer a convenient and economical alternative (e.g., thick nonwoven geotextiles or drainage geocomposites, of which there are many types and styles). Two recent field situations substantiate these comments.

At the site of a 100-year-old petroleum refinery currently being repurposed, a 60m × 20m (200ft × 65ft) surface impoundment was constructed using a 1.5mm (60mil) HDPE geomembrane on a lightweight geotextile used for puncture protection. It was not vented and within a few months many whales and hippos appeared, as seen in Figures 1A and 1B.

To remedy the situation, 220mm (9.0in.) (approx. 0.10 kPa [94 lb/ft2] normal stress) of gravel was placed and vents were cut in the geomembrane at the top of the slope. The gas in the whales and hippos was gradually forced out and the geomembrane returned to its original horizontal position. Their future occurrence is unknown at present.

A second similar surface impoundment was constructed at the same site but the geomembrane was underlain by a drainage geocomposite leading to 16 vents along the perimeter at the top of the slope. No whales or hippos appeared at this location (see Figure 2B).

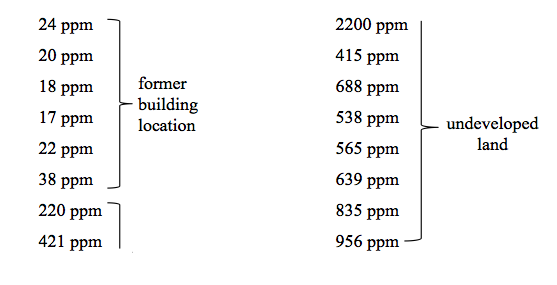

What the vents also provide, however, is direct access to the escaping gases for monitoring purposes (see Figure 2A). Using a MiniRAE 2000 portable VOC monitor, readings around the perimeter of the site were as follows:

The first six [parts per million] low values occurred where a former building was located and the 10 high values were formerly undeveloped land with assumed, but unknown, hydrocarbon disposal.

This study of inadequate drainage beneath surface impoundments brings into question the nature of the rising gases in this and other similar situations. In the textbook Designing With Geosynthetics, 5th edition, the following possible causes are mentioned: (1) degradation of subsurface organic material, (2) rising water table levels from adjacent sources, (3) changes in barometric pressure, and now (4) rising volatile organic compounds.

Of course, leaks in the geomembrane can exacerbate the situation but only up to the level of the liquid’s surface. While these rising gas mechanisms are difficult to quantify to “design” for the required transmissivity of the drainage material, the attempt is necessary and an example problem of whale/hippo avoidance is given in the textbook mentioned (pp. 567–568 in the 5th edition).

As with many other situations where common problems have occurred, it seems to the authors that geosynthetic drainage materials and venting networks should always be used for geomembrane-lined surface impoundments.

Dr. George Koerner is director of the Geosynthetic Institute (Folsom, Pa.).

TEXTILES.ORG

TEXTILES.ORG