The regulation of coal ash (coal combustion residuals or CCR) has significantly expanded the market for geosynthetics within the United States. Further, there is interest in these regulations around the globe in every country using coal as an energy source. These regulations are the result of recent environmental incidents. The regulations call for the increased use of geosynthetic materials in both new and existing sites and facilities, for storage, remediation, and stabilization of those sites. This article highlights the path to regulation, presents the important factors of the existing regulations, and discusses the ongoing application of the regulations.

Use of geosynthetics in barrier, drainage, and stabilization applications of civil engineering is well established. This article illuminates the history of how these materials and recent regulations requiring their use have been promulgated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). These regulations have been influenced by prior performance of geosynthetic materials and the demonstrated benefits of geosynthetics in civil engineering. Also, several environmental incidents at sites where geosynthetics and proper engineering technologies were not used have provided an impetus for regulatory and legal action, and indicated the scope and scale of the potential environmental impacts.

Early regulatory history

The geosynthetics market, and the geomembrane industry in particular, received its first large growth spurt with the 1976 U.S. Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA). These regulations were issued in two sections, the first specific to material considered hazardous waste, the second addressing the long-term fate of solid waste. Hazardous waste has since become known as Subtitle C waste, and solid and most common household waste has become known as Subtitle D waste. There is another waste stream known as construction and demolition waste, or “C and D material,” which is not regulated under RCRA but is instead addressed on a state-by-state or local regulatory basis.

The second significant regulatory impact occurred in 1980 with passage of the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act, more commonly known as “Superfund.” This law not only increased demand for geosynthetic materials but helped to spur on large growth in capping applications, using geosynthetics as surface or near-surface barriers to prevent rainwater infiltration.

But what about coal ash? The proper place to begin this review is in 1980 with the passage by the U.S. Congress of what is known as the Bevill Amendment, named for former U.S. Rep. Tom Bevill, D-Ala. In passing the amendment, lawmakers revised RCRA by adding section 3001(b)(3)(A)(ii), the Bevill Amendment, to exclude “solid waste from the extraction, beneficiation, and processing of ores and minerals” from regulation as hazardous waste under Subtitle C of RCRA. Further, the law mandated an EPA study of the impact of coal ash on the environment. The EPA completed this study, and it was published in the Federal Register on May 22, 2000. The report states, “The Agency has concluded these wastes do not warrant regulation under subtitle C of RCRA and is retaining the hazardous waste exemption under RCRA section 3001(b)(3)(C). However, EPA has also determined national regulations under subtitle D of RCRA are warranted for coal combustion wastes when they are disposed in landfills or surface impoundments.”

However, the EPA determination for Subtitle D regulation was not heeded, and the absence of regulations for coal ash storage continued. Just before 1:00 a.m. on Monday, Dec. 22, 2008, a dike holding back coal fly ash slurry ruptured at an 0.34-km² (84-acre) solid waste containment area at the Tennessee Valley Authority’s Kingston Fossil Plant in Roane County, Tenn. The breach released an estimated 4,200,000m³ (1.1 billion gallons) of coal fly ash slurry. Subsequent direct cleanup and remediation costs have been estimated at more than $1.5 billion. This incident, other large-scale coal ash spills, and other issues with groundwater contamination at or near CCR storage facilities resulted in the EPA promulgating regulation of coal ash storage and significant companion actions on the legal, federal congressional, and other governmental fronts.

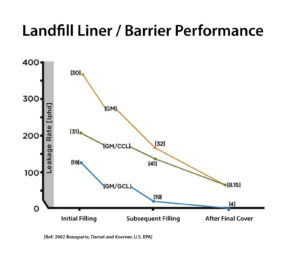

The most efficient and effective barrier system, one that is required by regulation, is a composite liner system using a primary geomembrane (GMB) liner, most commonly manufactured from high-density polyethylene (HDPE) with some form of clay, either a compacted clay liner (CCL) or a geosynthetic clay liner (GCL), although other variations exist. This is a direct result of that system being compliant with the EPA’s RCRA Subtitle D regulations.

However, the system(s) have a great history of success, as documented by several investigations, most prominently the EPA study titled “Assessment and recommendations for improving the performance of waste containment systems” by Bonaparte et al. (2002). Figure 3 illustrates the effectiveness of composite liners as indicated by lower leakage rates.

On June 21, 2010, after the Kingston spill, the EPA issued a proposed rule for the regulation of coal ash storage. But that proposed rule is factually inaccurate. The body of the EPA proposal contained at least three and perhaps as many as six different regulatory schemes, depending on how they were parsed. This confusion, combined with resistance to regulation in some quarters and the possibility of the classification of coal ash as a hazardous waste material, resulted in several years of political; legal; and governmental review, studies, proposals, and evaluations.

On October 31, 2011, another coal ash spill occurred at a power generation facility owned by We Energies on the shore of Lake Michigan in Oak Creek, Wis., south of Milwaukee. About 2,000m3 (500,000 gallons) of coal ash spilled, according to the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (Wisconsin DNR).

This accident released a significant quantity of coal ash into Lake Michigan. According to a report published by the Wisconsin DNR, the spill was the result of a sediment-retaining basin being built over old coal ash deposits. The report said, “The FGD [fluidized gas desulfurization] sediment basin would potentially be constructed in coal ash deposits. During construction, ash deposits were found in the western portion of the FGD sediment basin. These deposits were removed and replaced with suitable soil in accordance with the contaminated materials management plan. However, a liner plan was not submitted to the Department when ash deposits were discovered. A significant component of the bluff collapse material appears to be the coal ash deposited in a ravine in the 1950s–1960s.”

On Feb. 1–2, 2014, at least 30,000m3 (8 million gallons) of coal ash and stored contaminated water spilled from a closed pond at the Duke Energy power plant in Eden, N.C. The coal ash was transported through a failed drainage pipe below the surface impoundment into the Dan River.

The Dan River spill and the subsequent investigations were the impetus for two events with respect to the regulation of coal ash in the U.S. The first of these occurred on May 14, 2015. Duke Energy pleaded guilty to nine violations of the Clean Water Act (CWA) for illegally discharging pollution from coal ash facilities at five of its coal-fired power plants in North Carolina. The plea and negotiated settlement included payment of $68 million in fines and the expenditure of an additional $34 million for environmental and land conservation projects benefiting North Carolina and Virginia.

The federal judge in the case characterized the settlement as “the largest federal crime fine in North Carolina history.” Settlement documents said company shareholders would bear the costs, and they would not be passed on to Duke Energy customers.

North Carolina state regulations implemented

The Dan River spill also put in motion what may become a precedent-setting legislative response in North Carolina. By Sept. 20, 2014, the North Carolina General Assembly enacted the Coal Ash Management Act of 2014 (NC–CAMA). While surface water and groundwater pollution from CCR facilities were already regulated under authority of the CWA, CCR surface impoundments were unregulated repositories of solid waste.

In North Carolina, like many other states, CCRs in wet impoundment were not considered “solid wastes” and were exempt from the state’s solid waste disposal regulations. As a result, management practices likely to prevent pollution of water resources from CCR surface impoundments were neither mandated nor consistently applied.

NC–CAMA changed the regulation of CCR surface impoundments in North Carolina. The law required the following actions and set timelines for their completion. Until the enactment of NC–CAMA, nothing in then-existing state or federal law required any of these actions:

- conversion of utility ash handling practices from wet to dry ash handling

- cessation of deposition of CCRs in

wet impoundments - closure of all 33 CCR impoundments under prescribed environmental

standards

NC–CAMA required the assessment and prioritization by risk classification of all 33 CCR impoundments in the state. As of this writing, the North Carolina Department of Environment and Natural Resources (NC–DENR) has completed an initial final assessment. All of the CCR impoundments in the state were classified as either high or intermediate risks. Under the law, CCR impoundments in these classifications must be excavated and remediated. Excavated CCR materials must be beneficially reused or disposed as a solid waste in landfills or large-scale structural fills.

NC–CAMA also established stricter design, construction, and siting standards for large projects using coal ash as fill for construction projects and placed a moratorium on smaller structural fill projects. Essentially, large-scale structural fills are considered disposal units and treated similar to landfills.

CCR disposal in North Carolina must be carried out in a landfill that meets the most current standards for industrial landfills, including a composite liner system, leachate collection, groundwater monitoring, and financial assurance. NC–CAMA also provided acceptance of federal standards in the event the federal standards were more stringent.

The CCR Rule

As the regulations in North Carolina developed, the EPA continued its work on federal standards for CCR facilities. Despite efforts in the Congress to provide direction to the EPA and somewhat consistent with the consent decree resulting from the court case with Appalachian Voices et al., then-EPA administrator Gina McCarthy signed a final rule, Hazardous and Solid Waste Management System; Disposal of Coal Combustion Residuals from Electric Utilities (known as the CCR Rule), on Dec. 19, 2014.

The CCR Rule was ultimately published in the Federal Register on April 17, 2015, resulting in an effective date of Oct. 19, 2015. One of the fundamental foundations of the newly promulgated EPA CCR Rule was the continued exclusion of CCR from the list of hazardous wastes. While continuing the exemption, the EPA made clear it had not reached a final decision on regulation based on the Bevill Amendment.

While not listing CCR as a hazardous waste, the EPA stated in the CCR Rule, “The record is clear that current management of these wastes can present, and in many cases has presented, significant risks to human health and the environment . . . [and] the current level of risk clearly warrants the issuance of federal standards to ensure consistent management practices and a national minimum level of safety.”

Thus, since CCR is neither a listed nor characteristic hazardous waste under federal law, it can only be regulated per RCRA Subtitle D. Under the applicable sections of RCRA, the role of the EPA is the establishment of minimum national criteria that apply to CCR facilities. EPA fulfills its role by establishing the criteria and providing technical assistance to states to develop solid waste management practices for each state.

In the preamble to the CCR Rule, the EPA clarified its role:

“EPA has no role in the planning and direct implementation of the minimum national criteria or solid waste programs under RCRA subtitle D, and has no authority to enforce the criteria. While Congress developed the statutory structure to create incentives for states to implement and enforce the federal criteria, it does not require them to do so. As a result, subtitle D is also structured to be self-implementing. EPA also may act if the handling, storage, treatment, transportation, or disposal of such wastes may present an imminent and substantial endangerment to health or the environment, pursuant to RCRA section 7003.”

Although the EPA lacks authority to enforce the minimum standards, states and/or citizens have access to means to enforce the requirements of the CCR Rule. States may enforce the requirements of the CCR Rule using enforcement authority provided under state law. Both states and citizens may enforce the CCR Rule under the citizen suit authority provided within RCRA (and CWA). To facilitate monitoring and enforcement by citizens, the EPA included provisions in the CCR Rule requiring public access to owner-proposed actions and operational data.

As of Oct. 19, 2015, the self-implementing CCR Rule finalized enforceable minimum national criteria that owners and operators of CCR disposal facilities must meet to avoid having those facilities treated as open dumps under RCRA. The CCR Rule applies to certain CCR facilities located at or serving power plants owned by electric utilities or independent power producers actively producing electricity at those plants.

CCR facilities regulated under the CCR Rule include:

- new and existing CCR landfills and lateral expansions undertaken after the effective date

- new and existing CCR surface impoundments and lateral expansions undertaken after the effective date

- inactive CCR surface impoundments (in the published version of the CCR Rule, the EPA elected to create an incentive for more rapid closure of inactive surface impoundments)

With the establishment of the CCR Rule, the EPA ushered in several firsts regarding CCR facilities in the U.S.:

- regulation of CCR surface impoundments

- uniform minimum standards for landfill liner systems and cover systems

- uniform minimum standards for surface impoundment liners and

cover systems - regulation of large-scale CCR structural fills as landfills

The EPA also enumerated facilities and activities not covered by the CCR Rule. CCR landfills no longer in use and CCR facilities at power plants that have ceased all electricity production are not covered by the CCR Rule. In addition, the following activities are outside the CCR Rule:

- beneficial use of CCR

- placement of CCR at active or abandoned underground or surface coal mines

- disposal of CCR at municipal solid waste landfills (MSWLF)

After years of assessing the management practices associated with the storage and disposal of CCR, the EPA established the minimum criteria documented in the Code of Federal Regulations Title 40 Parts 257.50 through 257.107 (the Code).

The criteria are grouped into seven segments of restrictions and/or requirements the owners and operators of CCR facilities must comply with to establish new facilities, continue to operate existing facilities, and close and care for facilities at the end of their useful lives.

- Location restrictions

- Liner design criteria

- Structural integrity requirements

- Operating criteria

- Groundwater monitoring and corrective action requirements

- Closure and post-closure care requirements

- Record keeping, notification, and Internet posting requirements

The market for geosynthetic materials has been significantly expanded by the regulation of CCR facilities, the establishment of uniform minimum management practices across the U.S., the liner design criteria, and the closure and post-closure care requirements.

Boyd Ramsey is a former chief engineer and technical director for the Asia Pacific region for GSE Environmental, and now works as a geosynthetics consultant based in China.

Bill Betke is the director of business development for coal ash for GSE Environmental in Asheville, N.C.

References

Bonaparte, R., Daniel, D. E., and Koerner, R. M. (2002). “Assessment and recommendations for improving the performance of waste containment systems.” EPA/600/R-02/099. EPA National Risk Management Research Laboratory. <https://www.nrc.gov/docs/ML1217/ML12179A248.pdf>

“Coal ash recycling and oversight act of 2012’’ draft. (2014). Association of State and Territorial Solid Waste Management Officials. <http://www.astswmo.org/Files/Announcements/2012-08-Senate_Coal_Ash_Recycling_and_Oversight_Act.pdf> (Mar. 12, 2014).

“Dan River.” (2014). Wikipedia. Updated as of Mar. 6. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dan_River>

(Mar. 12, 2014).

Fettig, D. R. (2002–2006). Geosynthetics Market Survey. Geosynthetic Materials Association, Roseville, Minn.

Gabriel, T. (2014). “Utility cited for violating pollution law in North Carolina.” New York Times. Updated as of Mar. 3. <http://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/04/us/utility-cited-for-violating-pollution-law-in-northcarolina.html> (Mar. 12, 2014).

General Assembly of North Carolina. “Coal ash management act of 2014.” Session 2013. <http://www.ncleg.net/Sessions/2013/Bills/Senate/PDF/S729v6.pdf> (June 11, 2016).

Goss, D. (2010). “CCP beneficial use shows steady growth.” Ash at Work, 1.

“Hazardous and solid waste management system; Identification and listing of special wastes; Disposal of coal combustion residuals from electric utilities; Proposed rule.” (2010) Federal Register 75:118 (June 21), 35127–35264. <www.regulations.gov>

(Feb. 12, 2014).

Jones, M., and Behm, D. (2011). “Bluff collapse at Wisconsin powerplant sends dirt, coal ash into Lake Michigan.” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel/Engineering News Record, Nov. 1. <http://www.enr.com/yb/enr/article.aspx?story_id=165390983> (Nov. 3, 2011).

“Kingston Fossil Plant coal fly ash slurry spill.” (2011). Wikipedia. Updated as of Sept. 19. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kingston_Fossil_Plant_coal_fly_ash_slurry_spill> (Mar. 12, 2014).

Koerner, R. M. (2004). Geosynthetics Survey. Geosynthetic Institute, Folsom, Pa.

“Lack of lining in pond blamed in bluff collapse at We Energies site.” (2012). Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Updated as of Mar. 1. <http://www.jsonline.com/news/milwaukee/lack-of-lining-in-pond-blamed-in-bluff-collapseat-we-energies-site-f34ddln-141132423.html> (July 6, 2016).

Lombardi, K. (2009). “The hidden history.” I Watch News, January 7, The Center for Public Integrity. <www.iwatchnews.org> (Nov. 11, 2011).

Ramsey, B., and Aho, A. (2014). “Market impacts for geosynthetics from the regulation of the storage of coal combustion residuals in North America.” Proc., 10th International Conference on Geosynthetics, International Geosynthetics Society, Jupiter, Fla.

“Regulatory determination on wastes from the combustion of fossil fuels; Final rule.” (2000). Federal Register 65:99 (May 22), 32213–32237. <www.epa.gov>

Shoichet, C. E. (2014). “Spill spews tons of coal ash into North Carolina river.” Updated as of Feb. 9. <http://www.cnn.com/2014/02/09/us/northcarolina-coal-ash-spill> (Mar. 12, 2014).

“Summary of bluff failure We Energies Oak Creek Power Plant.” 2011. Wisconsin Dept. of Natural Resources. Updated as of Dec. 14. <http://dnr.wi.gov/topic/Spills/documents/oakcreek/nrbpresentation.pdf>

(Feb. 12, 2014).

“Technical amendments to the hazardous and solid waste management system; Disposal of coal combustion residuals from electric utilities—Correction of the effective date.” (2014) Federal Register 10:127 (July 2), 37989–37992. <https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2015-07-02/pdf/2015-15913.pdf> (June 11, 2016).

U.S. EPA. (2002). “25 years of RCRA: Building on our past to protect our future,” EPA-K-02-027, Washington, D.C.

U.S. EPA. (2009). “Bevill Amendment questions.” Updated May 1. <http://www.epa.gov/compliance/assistance/sectors/minerals/processing/bevillquestions.html> (Oct. 23, 2011).

U.S. EPA. (2011). “Fossil fuel combustion (FFC) waste legislative and regulatory time line.” Updated as of Oct. 20. <http://www.epa.gov/wastes/nonhaz/industrial/special/fossil/regs.htm> (Oct. 24, 2011).

U.S. EPA. (2011). “Information request responses from electric utilities.” Updated as of Aug. 16. <http://www.epa.gov/epawaste/nonhaz/industrial/special/fossil/surveys/index.htm#databaseresUlts> (Nov. 11, 2011).

TEXTILES.ORG

TEXTILES.ORG

This paper assumes that Coal Ash is a waste and not a resource. In many parts of the world coal ash is used as a filler for cement to make it go further in making concrete. It is also used in the geosynthetics world to make sand mixes easier to pump and prevent them from setting hard as they would with cement added. These and other usage options completely transform the attitude to dealing with Coal Ash.